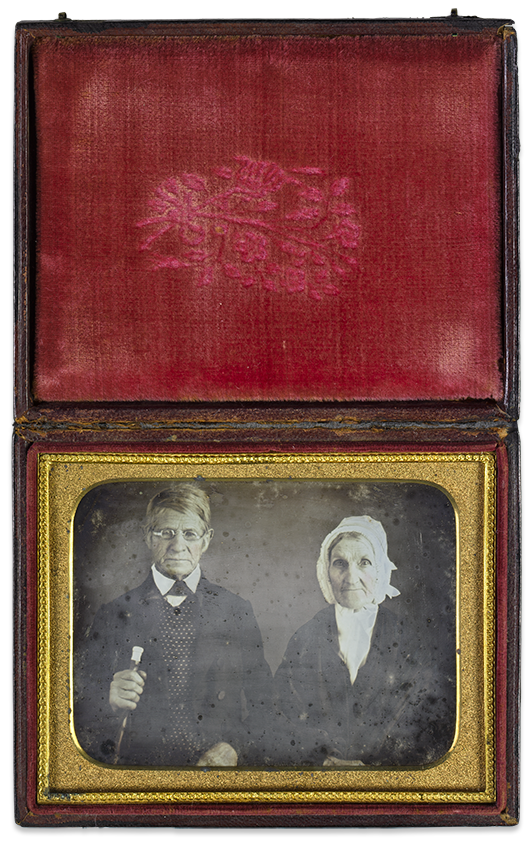

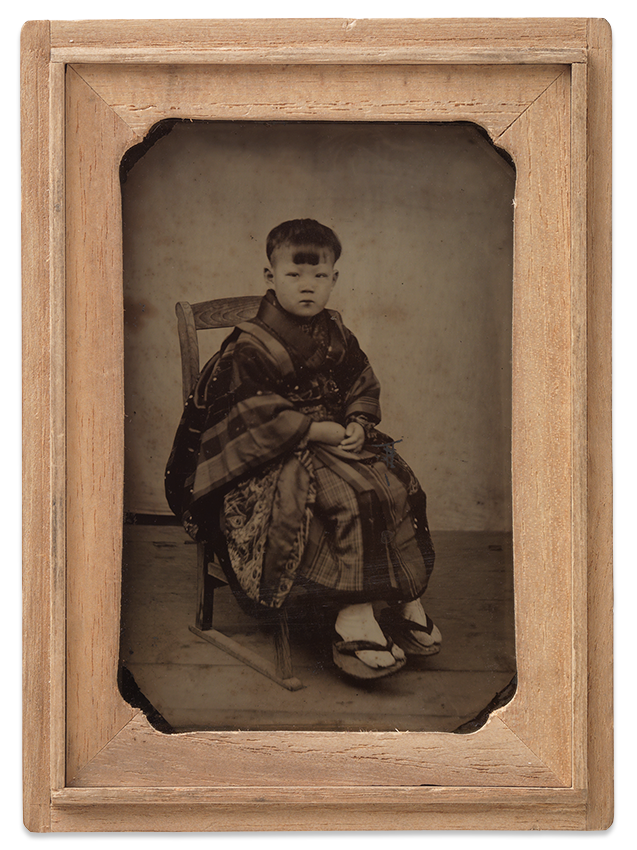

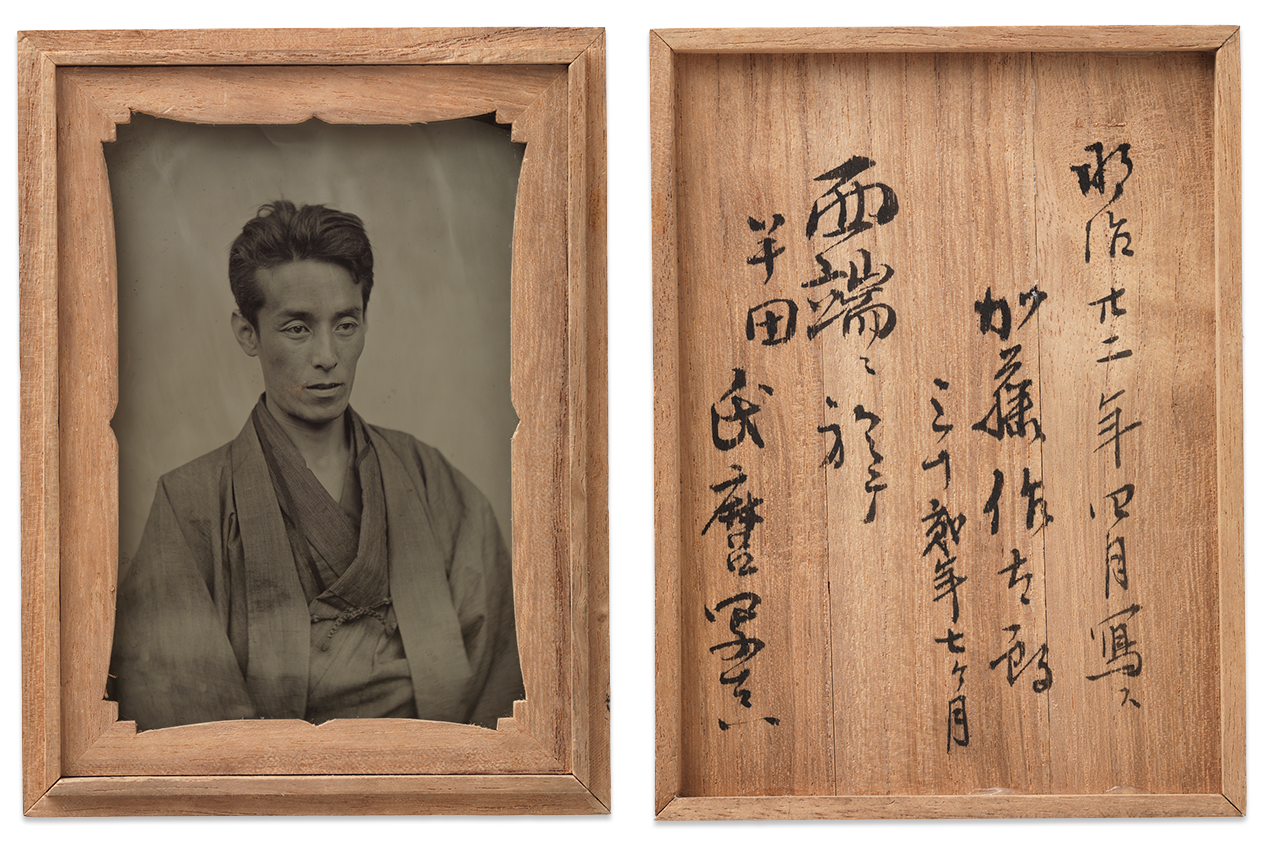

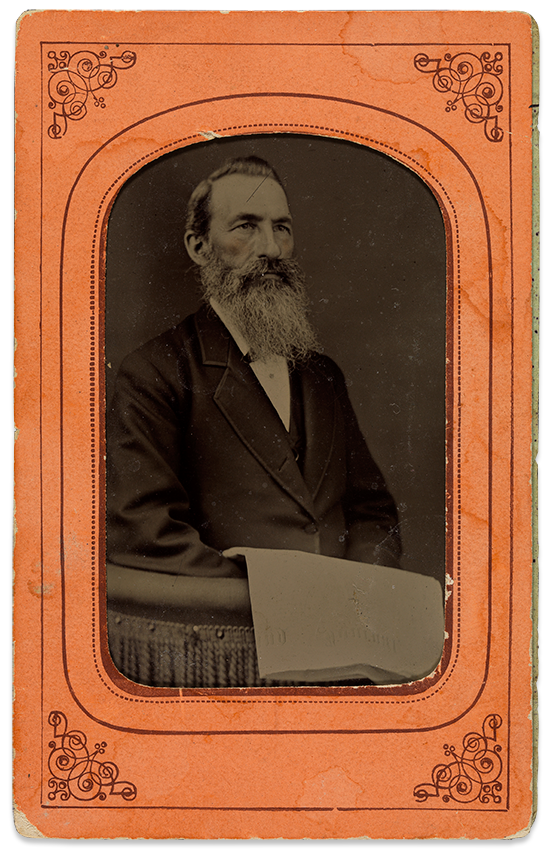

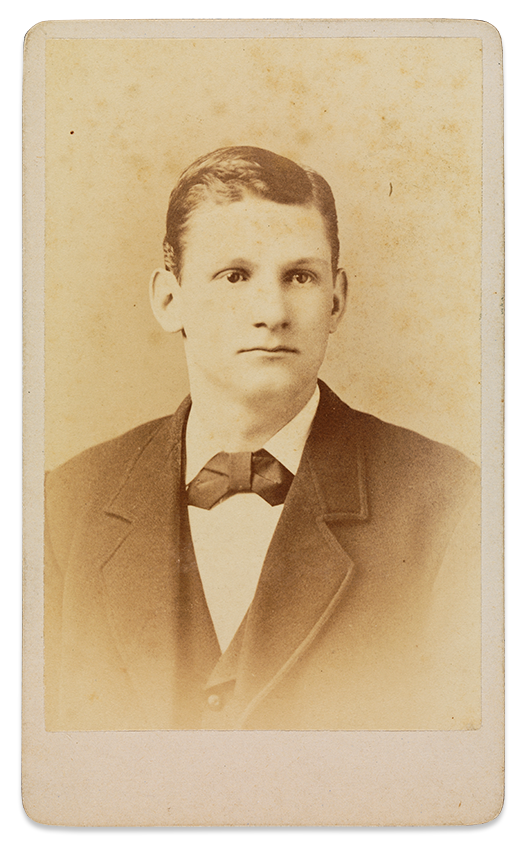

Unknown

United States

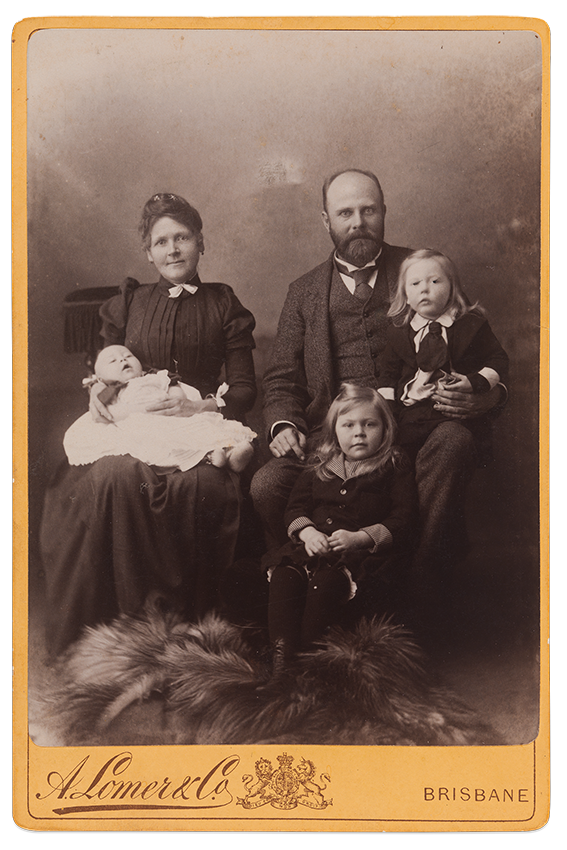

Mr and Mrs Caleb Morgan c.1850

Daguerreotype

Purchased 1991 with funds from

James Hardie Industries Limited through the

Queensland Art Gallery Foundation

Collection: Queensland Art Gallery

The first daguerreotypes were made in the United States in September 1839, just four weeks after Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre (1787–1851) revealed the details of the process at a Paris meeting of the French Academy of Sciences, in October 1839. While photographic studios soon appeared in major cities around the world, it was the United States which led the world in daguerreotype production.

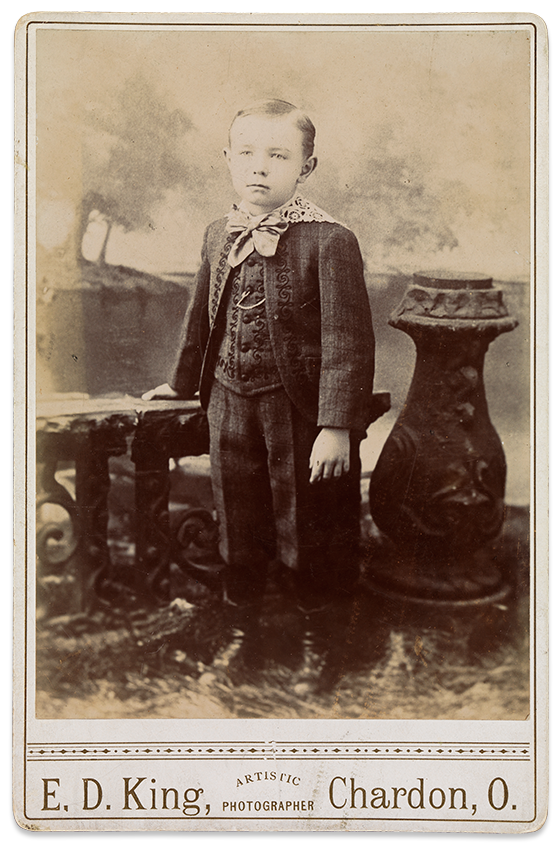

The earliest known daguerreotype photography studio opened in New York in March 1840 and, by the end of that decade, every sizeable American city had one, while smaller towns were serviced by travelling photographers, with covered wagons fitted out as mobile studios. Portrait photography was incredibly popular in the United States at this time.

The daguerreotype is a unique direct-positive image, made inside the camera on a highly polished copper plate coated with a thin layer of silver and iodine. Exposure time could be up to 25 minutes and the development of an image occurred when the plate was exposed to dangerous mercury vapours. The surface of a daguerreotype is like a mirror and, depending on the viewing angle, the image could change from positive to negative. As daguerreotypes are very fragile – the image can be rubbed off with a finger – they were kept under glass and housed in a protective frame or case made of wood and covered with leather and velvet.